7.42am

Someone is talking on the radio from the other side of the world.

They’re describing the streets of sort-of-opened-up London. They’re saying how strange it feels without all the tourists.

That’s your unavoidable truth right there. Whether we’d have locked our borders tight or not, the part of our economy that depends on visitors would be in a whole lot of pain right now. Nowhere, in the world right now, is tourism really happening.

The reason we’ve taken a substantial hit is: we had a whole lot of reliance on the tourists. The reason we’re not doing worse is: there’s a whole lot of the economy, thankfully, that is non-tourist.

Some immediate support can come in the form of New Zealanders spending their holiday money here instead of overseas. And, as hard and as intensely as we can, we need to really get to work on changing things, and looking for better ideas.

Question: what does really get to work on changing things mean? What might constitute a better idea?

Answer: well, not tax cuts and roads, that’s for sure LOL

10.00am

Pop-up leader of opposition announces big plan for making things better:

Tax cuts

Roads

No, it’s not a bribe.

No it will not be paid for in the customary fashion of underfunding everything else. How very jolly dare you.

11.11am

Wondering if we’ll be hearing more from the pop-up deputy leader who emerged from a Garbo-esque silence yesterday to declare that an eighth absconder from managed isolation suggested that this system - the one that has put through, what, 40, 50 thousand people? - is in disarray.

Well yes, I too have great unease. Why don’t I let a More Than A Feilding reader, who’s been working at an isolation facility, describe the complete mayhem they’ve been witnessing.

Nobody goes into the room other than the guest for the duration of the iso. Every time they even open the door to pick up their meals and then close it again they must be wearing a surgical mask.

and

The nurses do room to room health checks every day. Temp, questions etc.

and

Highly professional, very well run and thought out, constantly under review. Suggestions and questions welcomed, guests treated like VIPs.

Still it’s good to hear from old mate Gerry. The campaign just wouldn't be the same without his frisson of certitude and suppressed fury.

For some reason he went all quiet the same week the Court of Appeal delivered that judgement about Southern Response wilfully underpaying people by hundreds of millions of dollars. Perhaps now he’s feeling chatty again, he might be moved to comment on that outrage of hapless governance.

11.12am

Friend from the other side of seaside village Devonport is on my phone with a photo and a question.

I say no, I haven’t. I’ll check my letterbox. Nothing in the box, so she says here have a steaming pile.

Needless to say, it goes on and on and on and on.

She says who would do such a thing?

I speculate: someone old, pale, male and hateful?

Once, at drinks, at an Auckland TV channel, I met a columnist for an Auckland morning newspaper. As I leaned in to hear him better, taking care not to get too near the red wine sloshing unsteadily around his glass, I got that same stale smell of cigarettes and liquor you get as you come near to hear what your near-dead great uncle is wheezing at you.

You know the odour, eh. These pages have the same thing wafting off them, all steeped in resentment and prejudice and certitude.

A sad old man of this sort was also at it this week with a thing that in the loosest sense might be called a cartoon, expressing disdain for Matariki, and all who might imagine it to be a good thing.

The most dispiriting thing about this stuff is that every single time, because they repudiate every single part of it, it feels necessary to trudge all the way back to first principles and lay out the entire argument. And generally it’s a complete WOFTAM because they refuse to accept any of it.

They will roll out their specious fallacious rebuttals and they will fulminate without end. But it doesn’t make them right.

A while ago I wrote something that I thought I might turn to each time this happens. It doesn’t capture it all, but it’ll do for now, because honestly, I don’t want to spend any more time inhaling the odour of near-death.

1.09pm

Something to turn to each time this happens.

It’s never a long walk to find someone and three of his mates who think it’s time to move on and you’re talking about something we had nothing to do with mate and we're all just New Zealanders and no-one should get special treatment.

Not everyone says this. Many don’t. But there is a headwind, always, when tangata whenua assert their right to be heard, to take part; raise any objection to being overlooked, being denied.

There’s always something: Covid checkpoints, trees on maunga, occupation of Ihumatao, take your pick. And there are always people still saying it’s time to move on and you’re talking about something we had nothing to do with mate and we're all just New Zealanders and no-one should get special treatment.

I used to engage; in print, on talk radio, at dinner tables. These days I take a path of lesser resistance. I encourage people to watch TV or read a book.

Where could a doubter start? So many possibilities: the many Waitangi Tribunal reports; a TV series like The Negotiators; any of the hundreds of history books that walk back through the promises made and broken.

The usual ending to those reports and the TV and the history books is someone saying: I had no idea, or: we never covered this in school, or: did they really settle for just 5 cents in the dollar?

There was a Treaty. There was an understanding. And then there was very little of either. Through confiscations, shady dealings and laws that worked against the interest of Māori, the 66 million acres they had held in 1840 dwindled to 11,000 by 1890.

The first people of this land went to court, went to battle, never stopped asserting their rights, but the die was cast: the system of government and justice was set up to fail them. They went from being owners of nearly everything to almost nothing; pushed aside to the margin.

Where Māori eventually found themselves in the wake of this deprivation was: demoralised and lost. This was the damage of colonisation. It was a body blow. People can roll their eyes when you use the word, but that is what it was, and that is what it can do. It can cast the longest of shadows. The underemployment, the undereducation, the incarceration, the adverse health; all of it tracks back to what was done to the first people of the land: pushed to the margin, left to fade from sight.

What has been done in the last 40 years has been intended to restore, to mend, to make possible what was promised at the outset. It’s what justice demands, but it's not only that. It’s also a promise of something richer for us all.

A strong say in determining your future and a strong say about the issues that affect you is just basic democracy, let alone the fact that a treaty requires it. But you can go further than that as well. At a time like this, when so much is in flux and we have never had a greater need for fresh thinking, why wouldn't you make sure you were listening to Māori?

I see something richer, other people see a swamp.

In the time of plague, were we all in this together? Or did some old prejudices show themselves again?

Iwi set up covid-19 roadblocks. Some people saw vigilantism. They could equally have seen it as a community protecting its people stopping drivers and asking simple questions: Are you from around here? Are you an essential worker? Do you have a reason to be travelling under this level? And, if not: would you mind turning around and going back?

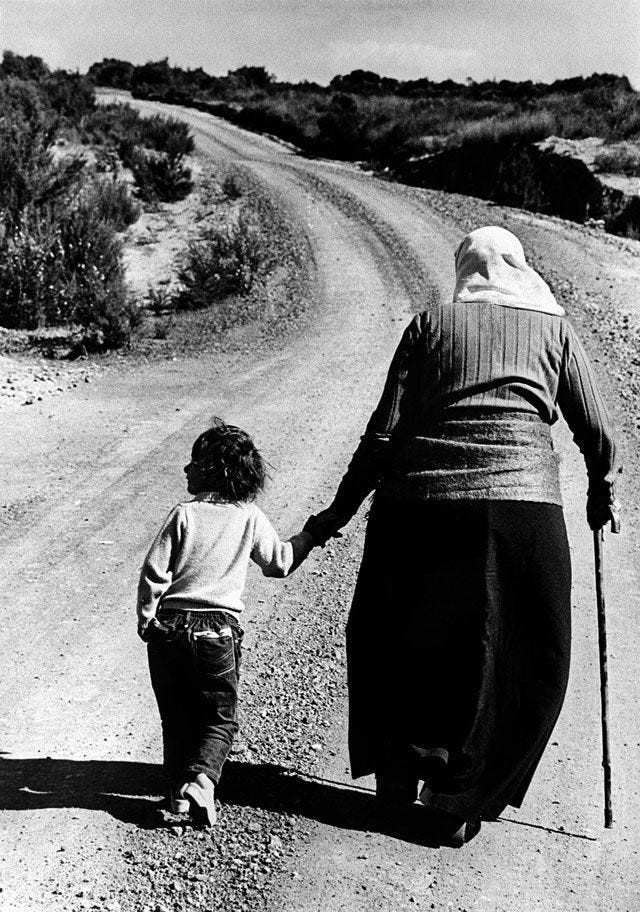

These were not outlaws running some shakedown. This was community care: swabbing, medical support, food parcels, looking after old people, ensuring your most vulnerable were protected, keeping out anyone who had no need to come in.

A person could lay out legalistic objections, but what’s the motivation, honestly? A passion for the rule of law? Or mistrust, prejudice, and unreasonable assumptions?

Justice minister Andrew Little was prepared to see it in constructive terms, characterising it as tino rangatiratanga in practice, which was to say: the treaty allows for self-governance, and here was a good example.

That mistrust and those unreasonable assumptions, though: they’re not easy to dispel.

Fully a third of Auckland's trees are reported to have been felled in the past decade, but the most noise of objection has been about the ones coming down in a small corner governed by the Tūpuna Maunga Authority.

The Authority's long term plan for Auckland’s Ōwairaka is to restore the maunga to its earlier state, planting thousands of native plants and trees. That entails taking out about 300 exotics because if you waited to extract them later, you'd likely harm the growing plants and trees.

The plan is to plant intensively to recreate a sense of what this place was like long ago, adding layers of richness to our surroundings and our culture. What's not to like about that? Why wouldn't you want to develop a stronger sense of our history and environment?

But the authority has found itself assailed and denounced. Never mind that the arrangement is the outcome of a treaty settlement, never mind that out of it has come a generous sharing arrangement; mistrust and unfair assumptions hang in the air.

And on it goes, always another issue, and every time once again more gainsaying of everything all the way back to the treaty and its promises and its breach, and the ramifications of that.

Why burn up all that angry energy again and again? Why not make the most of the possibilities instead?

Planning a future is a task for both parties to the treaty. You can see that as an imposition and impediment, or you can see the rich potential of it.

A doubter could gripe about the cost of the treaty settlements (about the same as the bailout of South Canterbury Finance) or they could consider how much good has followed. Consider for instance the role of Ngai Tahu in the recovery of Canterbury; consider the structures iwi incorporations have developed to care for their people's economic need and health; consider the outsize success of Maori exporters and enterprise; consider for even a moment, how much might be missing from any New Zealander’s cultural landscape without the rich dimension that is Māori.

None of this has to be difficult. Sometimes it may be a question of shared management, sometimes it may be a matter of consultation, and sometimes it will involve self-government. But always it will be a question of ensuring that special voice is heard.

It’s a crying shame your writing was dropped from that media outlet while certain unnamed dropkicks remain on the payroll.

Jeez yes, arguments worth reciting time and time again