More Less is More

Sunday column

The recurring heroes of Christopher Luxon’s sloganeering are New Zealanders who are working hard, trying to get ahead.

How valiantly they toil in the face of a useless government, just trying to get ahead.

Many people nod approvingly at such words. They, too, see it as noble and principled to be the kind of person who works hard to get ahead.

But what does it actually describe, this ideal?

If getting ahead simply describes outrunning misfortune, or bankruptcy, or a pursuing bear then, sure, I get it.

But we know that’s not what anyone’s talking about. This has altogether more to do with getting more, having more, the sure and certain hope that the more money and shiny things you have, the happier you will be, a spirit of sharp elbows and self-interest.

When you see things this way it becomes respectable, noble even, to see most everything as a transaction, the people around you as competitors.

What does it profit a man, to gain the whole world, and lose his own soul, we might ask.

We might also ask, with reference to not only getting ahead but also capitalism itself: Is this really the best we can do?

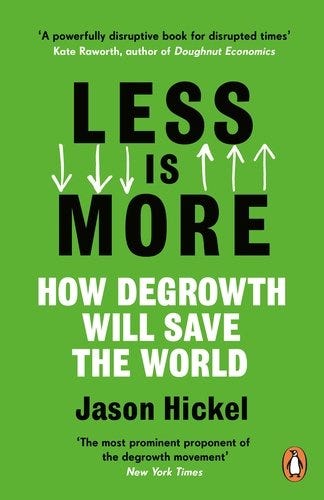

Welcome now, to the delayed second instalment ( the first is here) of an exploration of the compelling ideas raised in Jason Hickel’s Less is More — for that is where this riff on capitalism is taking us today — towards the altogether better world of Degrowth.

Economic Growth equals getting ahead, right?

Not necessarily.

We tend to take the idea of growth for granted, Hickel writes, because it sounds so natural. And it is. All living organisms grow. But in nature there is a self-limiting logic to growth.

We want our children to grow, but not to the point of becoming 9 feet tall,…We want our crops to grow, but only until they are ripe.

…This is how growth works in the living world. It levels off. The capitalist economy looks nothing like this. Under capital’s growth imperative, there is no horizon – no future point at which economists and politicians say we will have enough money or enough stuff. There is no end.

…The unquestioned assumption is that growth can and should carry on for ever, for its own sake.

And he describes the fatal flaw. Three per cent growth means doubling the size of the global economy every twenty-three years. And then doubling it again, from its already doubled state. And again. And again. Thus do we find ourselves at the point of redlining, as we consume ever more energy and resources.

If you’re braced to read that our only option now is to all embrace a monastic existence, the news is altogether more encouraging than you might hope.

The thesis of Degrowth is that we don’t have to forgo an agreeable way of life, we just have to let go of the getting ahead ideas that are carrying us over the cliff: the belief that no matter how rich a country becomes, its economy must keep growing, that we need growth in order to improve people’s lives.

The thesis of Degrowth, which we touched on last time, is that beyond a certain point, which high-income countries have long surpassed, the relationship between GDP and social outcomes begins to break down. Past a certain point, more GDP isn’t necessary for improving human welfare at all. What’s needed instead is reduce inequality, invest in universal public goods, and distribute income and opportunity more fairly.

When people live in a fair, caring society, where everyone has equal access to social goods, they don’t have to spend their time worrying about how to cover their basic needs day to day – they can enjoy the art of living. And instead of feeling they are in constant competition with their neighbours, they can build bonds of social solidarity

The thesis carries on a little further to underline the point, to consider not only what makes people happy in their life but what gives it meaning. To nutshell the data: it’s not the fleeting rush you might get from how much money you have, or how big your house is, it’s the deeper stuff: the opportunity to express compassion, co-operation, community and human connection.

In 2012, a team of researchers from Stanford School of Medicine visited the Nicoya Peninsula in Costa Rica to try to make sense of some fascinating data coming out of that region.

We know that Costa Ricans live long lives: around eighty years on average. But the researchers had noticed that Nicoyans live even longer, with a life expectancy of up to eighty-five years – one of the highest in the world. This is odd, because Nicoya is one of the poorest parts of Costa Rica, in monetary terms. It is a subsistence economy where people live traditional, agricultural lifestyles.

So what explains these results?

Costa Rica has an excellent public healthcare system, so that’s a big part of it.

But the researchers found that Nicoyans’ extra longevity is due to something more. Not diet, not genes, but something completely unexpected: community.

The longest-living Nicoyans all have strong relationships with their families, friends and neighbours. Even in old age, they feel connected. They feel valued. In fact, the poorest households have the longest life expectancies, because they are more likely to live together and rely on each other for support. Imagine. People living subsistence lifestyles in rural Costa Rica enjoy longer, healthier lives than people in the richest economies on Earth.

North America and Europe may have highways and skyscrapers and shopping malls, huge homes and cars and glitzy institutions – all the markers of ‘development’. And yet none of this gives them a shred of advantage over the fishermen and farmers of Nicoya when it comes to this core measure of human progress.

Over and over again, we see that the excess GDP that characterises the richest nations wins them nothing when it comes to what really matters.

Okay, all lovely, but back in the real world where we’re doing the hard yards and just trying to get ahead, who’s going to be inventing any new cell phones or fricken laser beams if there’s no capitalism? Eh? Eh?

The Degrowth thesis responds: bro do you even lift?

It’s important to remember that many of the most important innovations of the modern era, including truly life-changing technologies we use every day, were funded not by growth-oriented firms but rather by public bodies. From plumbing to the internet, vaccines to microchips, even the technologies that make up smartphones – all of these came from publicly funded research. We don’t need aggregate growth to deliver innovation.

Okay, I’ve now spent two instalments just looking at the fatal shortcomings of capitalism and infinite growth without even barely describing the proposed alternative, and how it might ever be implemented.

But keeping to my approach of not attempting to eat anything larger than my head, I’ll hold that to the next instalment, save to quote just this:

Degrowth is a planned reduction of excess energy and resource use to bring the economy back into balance with the living world in a safe, just and equitable way.

Never mind getting ahead, how about we all try to get there together?

While a positive concept which really appeals to me, it seems depressingly impossible to occur. I often think back to the dawn of Covid - if the world had truly acted as a community we could have seen it off in 3 months. However, the “what about the economy” and the parochial concerns about international competitiveness soon burdened us with decades of Covid waves. A direct shot into the left foot by the right.

For some time now, my response to the whole "Hard working folk, trying to get ahead" trope has been, "Trying to get ahead of who?"

This tends to perplex the utterer...