My daughter and I are noisy people, the way my dad's father and his father were. Dad is quiet. He treats his words as though they cost ten dollars each. People think well of him.

I have friends who still feel the sting of a father who was cold, or manipulative, or feckless, or violent, and mine was not one of those things, ever, just good and decent; a provider, a quiet perfectionist.

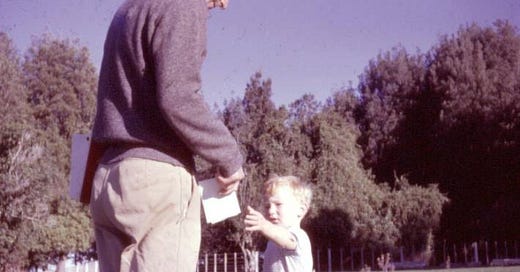

I trailed around after him all over the farm in my little gumboots, as he drenched sheep, drafted them, spent hours in the woolshed preparing them for ram sales and royal shows.

Whatever had to be done, however much it might take, however tough it might be, David Slack's Dad just kept going, sometimes grim but, mostly, with a joke or a rueful laugh.

He was always working. I was five when we took our first holiday at Waikanae beach. I jumped out, inspected the bach, came back to the car, puzzled, and said: "there's no woolshed for Dad."

If something needed to be said or explained, he'd say it, but then you'd be in silence again, and it was fine. I just watched and learned: this is how you putty a window, how you mow hay, how you split kindling, how you set a fire, how you lean into the rain and keep walking.

I would stand in my little gumboots as he slaughtered a sheep each week for the table and the blood ran deep red. I would follow behind him in the morning half light in duck shooting season and there was the gunpowder smell of the spent cartridges and the sheen of the feathers as he plucked them, until the day he decided it was just too cruel to the ducks and left them alone.

But he was a stockman who knew why you raised fine animals and he was very good at it.

And one time there were two sheep penned ready to be slaughtered and the neighbour's kids and I were prodding and taunting them, these poor animals waiting in the pen, and I can't tell you why we were doing it apart from the cruel delight of the bully, and Dad found us doing it and he didn't use many words but I never felt more ashamed and wrong.

He loved horses, raised them, rode them, admired them, and he would show the most excitement, ever, when a champion was sweeping towards the winning post. But he hardly ever put even a dollar on them because everything, his food, his drink, his health, was done in sensible proportions. These are lessons I took a long while to learn.

Everything happened at a considered pace. It could drive me wild with impatience but he just went carefully, patiently, methodically, and sometimes that meant we would be out at midnight still bringing in bales and stacking them in the hayshed.

Whatever had to be done, however much it might take, however tough it might be, he just kept going, sometimes grim but, mostly, with a joke or a rueful laugh. Cheerful, stolid.

We were standing in a kiwifruit packhouse once, the two of us, methodically going through his crop, sorting reject fruit, knowing the best he could expect from this cost saving was a smaller loss. Some guy in a company car came powering down the long gravel drive putting up a cloud of dust, clearly very pleased with himself and his great importance. The two of us lifted our heads, clocked him, both at the same time said: "wanker" and went back to sorting.

And now he's 93, and still gets around alright but his memory runs short and he's feeling pain more often than not.

On Christmas day Mum said, "Dad would like to say hello" and he came to the phone. We talked about plans for the day and our girl about to leave for London, and then he said he thought he might be getting pretty near the end of his run, and laughed and said "we all come to it" and it was a laugh to put you at ease, because what can any of us do, but also you think after you've finished talking that you want to say more, and so here it is: a letter to my Dad in the paper, telling him we were just as lucky as anyone could be to have him and there you go Dad, I got someone else to pay for the words.

My Dad and yours would have been good mates if they'd met; their lives a different dance but to the same beat. I've tried my best to be like them, but I've come up bit short. Not that they'd be anything other than quietly supportive of the effort. My elders and betters.

Lovely piece David,